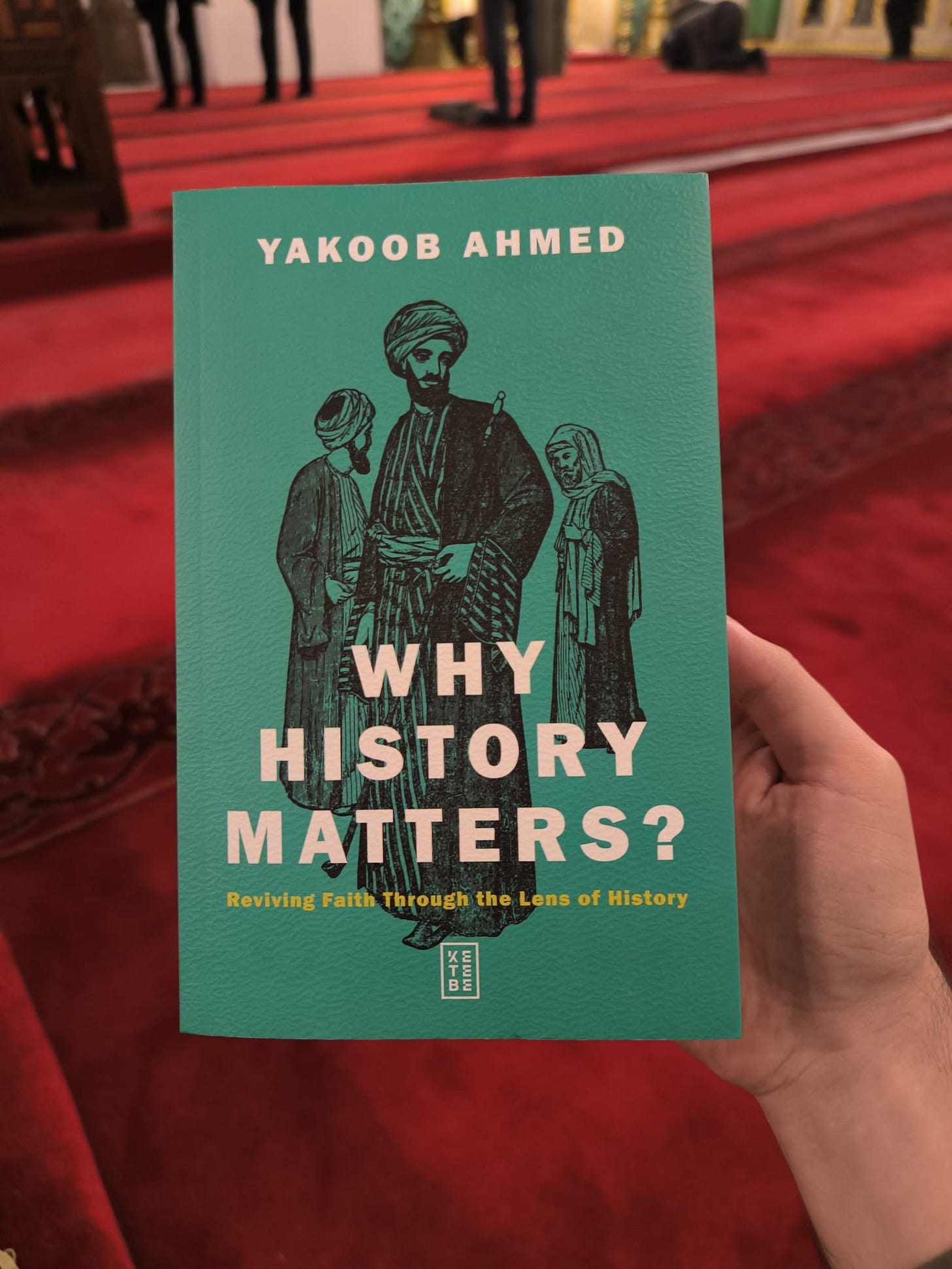

Why History Matters?

The Journey of my first book

(Bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm)

How This Book Came About

A Strange Beginning

How did this book come about? To be honest with you, it’s a bit of a strange story. I wasn’t planning to write this book at all. I was actually deep into another project — my first manuscript on the Ottoman Empire — when Ömer Faruk, who works at the publishing house Ketebe, came to see me.

We spoke for a while, and then he made a proposal that caught me completely off guard:

“Would you be interested in writing a book on why Muslims should study history?”

I paused. It wasn’t something I had considered before. I thought to myself, Is this something I can do? Is this something I want to do?

Ömer, however, had more confidence in me than I had in myself. I don’t know whether it was imposter syndrome or something deeper, but I wasn’t very sure of what I could offer. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe in the subject — I did, deeply — but I wasn’t sure if anyone would care to read it. Would Muslims really engage with these ideas? Would they find meaning in them?

Seeds of Doubt

In the past, I had already encountered resistance from within the Muslim academic world. Some felt that my approach wasn’t “academic enough”, that I should tone down the spiritual or moral dimensions of my thinking.

But I wanted to find a way to express myself differently, to articulate what I had been teaching and believing for years, but in a more direct and heartfelt way.

Ömer gave me that opportunity. He invited me to his offices, and as we spoke some more, I could see that he truly believed in this project. He believed in me, and more importantly, he believed in Allah’s plan for us. His belief gave me courage when my own was faltering.

The first draft I wrote was really just a thought experiment, an attempt to see if this vision resonated with anyone else. It really was a bit of a mess, as random ideas and thoughts were placed on the page. I feel sorry for the editor who went through that first draft and am grateful for their help and comments. But after all that, I still remember what Ömer told me during one of our early meetings:

“Don’t worry about it. You just write it — and let Allah do the rest.”

Those words stayed with me. They really did. It felt like I was hearing my own advice.

The Power of Du‘a

When I went home that evening, I reflected deeply on what he said. Truly, inspiration comes from Allah, though not always in the ways we expect. And being inspired by Allah doesn’t mean your ideas and works need to be perfect, or that you will not be tested. If only people knew, I stayed awake nights, writing this book, while writing my manuscript at the same time. This was a labour of love; it was a book that people encouraged me to write, and yet I had put off due to my own insecurities. I turned to my friends and students, and they were so excited. I couldn’t let them down; I could at least try. Inshallah, this will allow me to go further.

I often tell my students to make du‘a, to ask Allah for guidance and inspiration. One of them once said to me, “But how do I know Allah is listening?”

I told them, “The mistake you’re making is treating du‘a like a transaction. You’re focused on the outcome — Will I get what I asked for? But du‘a isn’t only about the result. It’s about the act itself — the act of turning to the One who created you. It’s a spiritual act of humility and recognition.”

The very fact that you were inspired to make du‘a is proof that Allah is listening. Where did that thought come from, that impulse to turn to Him, to raise your hands, to ask for help? That inspiration comes from Allah Himself.

If He permitted you to turn to Him, then of course He is listening. Whether He gives you what you asked for, delays it, or replaces it with something far better — He has already heard you.

Our job is not to measure His response, but to trust in His wisdom.

That reflection gave me peace, and with it, courage. I thought to myself, I’ve been teaching these ideas for years. Perhaps it’s time to write them down, no matter how imperfect.

A Book with Intention

From the beginning, I knew this book wouldn’t be perfect. It wasn’t meant to be. It was meant to start a conversation, and somewhere down the line I lost track of that. It was another Omer in my life who reminded me of this. My friend Omar Sheikh said,

“Doc, you don’t need to think about whether this will sell or not; you just store your thoughts in a place (the book) that starts that conversation that you have already started before writing. The rest will be part of the journey. This is not about you; it is about the ideas.”

He was right, it wasn’t about me, or about book sales, or about carving out an academic niche. It was about making the case for something I have always believed in: that Islamic history, and indeed, all history, can be written from an Islamic perspective.

What that means is that our sacred sources, the Qur’an, the Sunnah, and the intellectual traditions of our scholars, can guide, inspire, and structure how we understand the past. They can offer more than just critical analysis; they can give us meaning, ethics, and purpose.

When I was working on my academic manuscript, I realised how often the ‘ulama of the late Ottoman Empire were misunderstood, perhaps unintentionally, perhaps not. My research led me to very different conclusions from those widely accepted in Western academic circles.

But even then, I found myself asking: What does this really do for the Muslim community?

Beyond highlighting a historical misrepresentation, how does this kind of work strengthen a believer’s faith? How does it help a Muslim understand their moral compass, or bring them closer to Allah?

That’s when I realised that much of my academic writing, though about Islam, wasn’t from Islam and its tradition.

Faith in the Margins

In academic settings, I wasn’t allowed to say, “Allah says in the Qur’an.” Such phrases were considered unacademic, even biased. I found that deeply troubling. It stripped away my agency to write from the very moral and spiritual foundation that animated the people I was studying.

And yet, when I read the writings of Muslim scholars from the Ottoman period, those I was researching, they were writing from faith. Their analysis, their reflection, and their conclusions were all rooted in the Qur’an, the Sunnah, and the ethics of Islam.

So I began to ask myself: Can I write not merely as a historian who happens to be Muslim, but as a Muslim historian?

That distinction is crucial. As a historian who was Muslim, my faith shaped my intuition; it made me sensitive to inconsistencies, to biases, to false assumptions about Muslim figures. But I could never say so openly. I couldn’t use revelation as a lens. I couldn’t quote hadith as moral insight.

That was what was missing.

Writing from Iman

This book is my attempt to change that, to write history that is Iman-oriented, that speaks from faith rather than merely about it. I remember speaking to another close friend of mine, also named Omar — Omar Sharif, to be exact. (That makes three Omars in this blog post, may Allah be pleased with al-Farooq (RA), and may the Ummah continue to celebrate him!) Omar Sharif has supported me every step of the way and reminded me that all of this is part of the journey. To write in an Iman-oriented way, he said, you must first have Iman.

What he meant was that I needed to trust the process, myself and Allah’s plan, both good and bad. It wasn’t about becoming personal about the book, but recognising that I was simply a vehicle for it, and letting the ideas do their own thing. We authors worry too much about our works not being perfect, which can sometimes hinder us.

Of course, it’s imperfect. There are parts that are repetitive because I wanted to drive home certain ideas. Other parts are exploratory, because I was testing the boundaries of what’s possible when writing from this perspective.

But at its heart, this book is an invitation — an opening, and at the heart of it, it is sincere.

I wanted to show that the Qur’an, Sunnah, and Sirah are not just devotional sources; they are instructive. They can shape how we think about history itself.

I wanted to revisit some of our classical ideas — such as cyclical theories of history — that are often dismissed today, and ask whether they still have value. I wanted to argue that Islam, as a civilisation, should not be reduced merely to art, architecture, and science. It also encompasses politics, ethics, scholarship, and the lived experience of the ummah.

And finally, I wanted to reflect on the relationship between history and fiction.

History, Fiction, and Imagination

I’ve always believed that Muslim writers should engage more with fiction, but not by imitating others. I don’t want us to produce “Islamic versions” of Star Wars or Lord of the Rings.

I want us to write stories that emerge from our own imagination, our own cultures, our own ethics, our own traditions.

At the same time, historians can learn from fiction writers, from their mastery of narrative, storytelling, and character development. And fiction writers can learn from historians, from our discipline, structure, and grounding in truth.

Both forms, when used responsibly, enrich one another.

An Invitation to Conversation

This book, then, is a conversation starter. It’s not a finished argument. It’s the beginning of a dialogue between academics, students, scholars, and readers who care about the future of Islamic thought.

Even the style in which I’ve written it — reflective, conversational, personal — is intentional. It’s the way I teach, the way I think, and, in many ways, the way I pray.

Insha’Allah, the book will be released in the coming weeks, with launches planned in London, possibly Turkey and the United States, ahead of Ramadan.

I wrote it as a form of sadaqah jariyah — a continuous charity. I wrote it for the Muslim reader, with sincerity, with care, and with love for this ummah, for this vocation, and for Allah Ta‘ala.

And if nothing else, I hope that comes across.

Thank you all for all your support, I hope that you find some benefit in what I have written, inshallah.

I believe also that re-engaging with our history is vital for us at this time, and in a way that is more culturally relevant to us as Muslims.

I also know how difficult it is to get these stories and perspectives out into the world via the mainstream publishing route. If our imposter syndrome as writers won’t throw a spanner in the works, those rejections from agents sure as hell will. And for that reason, I’m grateful you had all those Omar’s encouraging you.

Looking forward to getting a copy of this, inshallah.

I always panic when I read the news (and I used to be obsessed about reading the news and being "well-informed") and my brother (a history major) is almost always calm. Haha. (He says having a historical lens,y ou can kind of see how things will go, and he believes in the cyclical theory too.)

I love speaking to him and getting the historical perspective or really just to answer the question of "how did we get here?", whatever here is with the state of the world. It is really crucial to know before we can get into any solution-finding project. He's really piqued my interest in history and I'm really excited for your book!