Rethinking Time:

Between the Cosmos, the Clock, and the Sacred

(Bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm)

Lately, I’ve found myself drawn to the notion of time. When most people think about time, they think of clocks, calendars, or the ticking countdown of seconds. It’s often seen as something mechanical, scientific, or digital. Yet for historians, time is much more than that — it’s the very medium we work in.

We are, in a sense, time travellers. We study the past, observe the present, and often try to anticipate the future. When we reinterpret history, when we shift the way people understand the past, we inevitably influence how they see the present and imagine the future. The past, the present, and the future are not separate compartments; they constantly reshape one another. In that sense, history itself is a form of time travel.

The Language and Layers of Time

My recent readings have taken me beyond history into how different cultures, languages, and disciplines think about time. In Arabic and other Islamicate languages, there isn’t just one word for time. There is zaman, waqt, marra and others — each carrying its own shade of meaning.

This multiplicity fascinates me. It shows that time isn’t a single, fixed idea but a spectrum of experiences from the momentary to the eternal, from the measured to the divine.

Watches, Craftsmanship, and the Art of Measuring Moments

This curiosity led me down an unexpected path, into the world of watchmaking. I recently picked up a beautifully designed magazine, possibly published by a team from the UAE called Arabic Numerals, for avid watch collectors. Its title caught my attention because it immediately reminded me of Ottoman-era clocks inscribed with Arabic numerals, a small but profound marker of cultural heritage. I’d never seen a title like that, and I went through its contents, becoming intrigued by how watchmakers think about time, mechanics, design, and fashion.

Within its artistic pages were interviews with watchmakers and collectors, modern artisans deeply preoccupied with time. One figure stood out: Xhevdet Rexhepi, (Cevdet Recepi in Turkish) a Kosovar-Swiss watchmaker whose work embodies a poetic relationship with time. I want to quote from the magazine what they said about his work.

“In one of his creations, the Minute Inertia, the second hand pauses for two seconds at twelve o’clock before allowing the minute hand to jump forward, a gesture inspired by Swiss train station clocks. That momentary pause, that breath before the next minute begins, struck me as symbolic. It reminded me that even in our precise measurement of time, there remains space for rhythm, patience, and beauty.”

This made me realise not simply the movement of time but the idea of the pause, that space where one could say time skips a beat, or freezes or stays still, even if it is for a second. For me, the idea of time stalling, or to imagine it, does fascinates me.

Timekeepers of the Ottoman Empire

When clocks first became widespread in the Ottoman Empire, particularly under Sultan Abdülhamid II, they were far more than tools for measuring time. The Sultan commissioned clock towers across the empire, from Istanbul to the farthest provinces, symbolising both the modernity and unity of the Ottoman domains.

Each tower was a statement of imperial vision: a blend of art, science, and sovereignty. Through them, Abdülhamid II expressed not only the empire’s embrace of technological progress but also his understanding of time as a form of order, political, spiritual, and aesthetic. Yet, while these towers shared a unifying purpose, each reflected its local culture and artistry, mirroring the empire’s rich diversity.

Beyond architecture, the Ottomans had two distinct figures devoted to the regulation of time. The first was the Müvakkit, the official timekeeper. Each morning after Fajr, the Müvakkit would adjust the public clocks by a few minutes to align with the day’s changing sunrise, following what was known as ‘ala turka time. This delicate daily calibration connected human life to celestial rhythm, a subtle dialogue between the mechanics of the clock and the movement of the heavens.

While the role has largely vanished today, some say a similar practice continues in Medina, where time is still lovingly tended with spiritual precision.

The second timekeeper was one we often overlook: the Mu’azzin. Through the adhan, the call to prayer, the Mu’azzin marks the passage of time — not through mechanical instruments but through the human voice. Even when the movement of the sun is hidden by clouds or climate, the Mu’azzin reminds the community of its temporal and spiritual rhythm.

Time as a Sensory Experience

It’s not just sound and time that I became interested in; another entry in the magazine that fascinated me was the interview with Ali Zainal, a Bahraini collector passionate about vintage watches designed for the visually impaired. These watches, created before the era of glowing screens, allowed users to feel the time through touch or subtle vibrations. Zainal explained that these watches and clocks weren’t designed for blind people, however, but were initially designed for people who couldn’t see the time at night.

It’s one of the reasons why many traditional clocks are designed to chime, their bells marking the passage of time even when unseen. The beauty of the mechanical clock lies not only in its precision but in the subtle language of sound and motion it speaks.

Every click, whirr, and shift of the gears tells a story. To the trained ear, the strike of a bell at noon or the half-hour signal, the steady beat of the second hand, or even the faint grinding of the mechanism, reveals the hour without the need to glance at the dial. These timepieces were, in a sense, audible instruments of time, each tick and tone a reminder of the rhythm of life itself.

Some watches went even further: they didn’t chime at all, but instead communicated through touch, sending gentle vibrations to the wrist to indicate the hour. Time could be felt, not just seen or heard which made it a profoundly human way of connecting to its passage. In an age where everything must be seen instantly, this tactile connection to time feels almost revolutionary, a return to a more intimate, embodied awareness of the passing hours.

From Mechanical to Digital — and Beyond

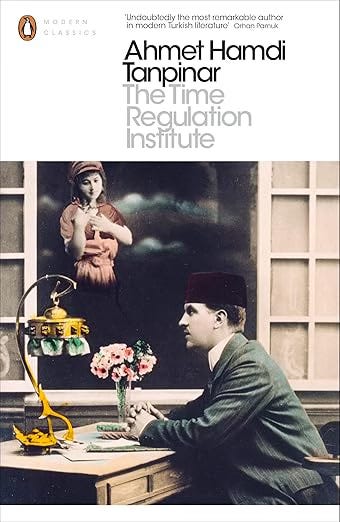

Reading these reflections on mechanical clocks made me think of Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, the Ottoman-Turkish novelist who lamented how modernity and the mechanical clock alienated us from natural and cosmic rhythms. Ironically, the very device once criticised for its artificiality — the clock — now feels like a symbol of craftsmanship, tradition, and humanity in the face of digital abstraction.

Tanpınar speaks powerfully about the notion of time, how modern life has stripped us of the luxury of idleness, of the simple ability to waste time or be bored. The mechanical clock, he suggests, distanced us from nature’s rhythms, from the cosmic clock that once governed our days through sunlight, shadow, and season.

Looking at our own age, I can’t help but notice how this separation has only deepened. We take the digital clock for granted, its silent precision, its constant presence on every screen, yet in doing so, we’ve lost something profoundly human. The mechanical clock, with its ticking heartbeat and visible motion, once symbolised our mastery of time; now it struggles for relevance in an era defined by digital abstraction.

And yet, ironically, I find myself drawn to the mechanical clock. What was once criticised for detaching us from natural time now feels like a bridge to tradition, craftsmanship, and contemplation. I have become, perhaps, more antagonised by the digital clock, not for its accuracy, but for what it represents: a world where time no longer breathes.

Today, our lives are governed by digital clocks, deadlines, and data; it is precise but detached. The ticking clock once connected us to rhythm; the silent screen has removed that pulse. As I reflect on this transition, I find myself nostalgic for a time when time itself felt alive.

The Architecture of Time

The magazine also featured a remarkable Saudi architectural project called Sun Path, an installation at Jeddah Airport by Civil Architecture. It’s essentially a modern sundial, a space where moving shadows tell the time. The architects described how time shapes all their work, from tidal movements to the seasonal cycles of plant life.

They wrote:

“Time has always been an underlying theme in our projects… whether in a physical installation like the sundial or in the daily rhythms of practice. Underlying time helps us navigate both design and the world at large.”

They went on to say:

“It (time) reflects a broader evolution in our practice. We’re reaching a point where we’re thinking more critically about the nature of time, not just in architecture, but in our own works. Over nearly a decade, we’ve started to see patterns emerge, the rhythm of exhibitions, the flow of projects, and the accumulation of ideas over time. Understanding these cycles allows us to better structure our work.”

Their words resonated deeply with me. As I’ve been studying cyclical theories in Islamic thought from Ibn Khaldun to Malik Bennabi and I’ve come to believe that time is not purely linear. In Islam, time is profoundly cyclical: it turns, returns, and renews.

Time, Cosmos, and the Sacred

Islamic spirituality is deeply intertwined with cosmic time. Our Hijri calendar follows the moon, not the sun, a celestial rhythm visible to anyone who looks up. The lunar phases mark our months, and even our daily prayers are bound to the movement of the sun.

The Islamic calendar is lunar, anchored to the movement and phases of the moon. Even without a written calendar, one can look to the sky and know where they stand in the month by observing the crescent’s birth, its growth, its fullness, and its fading.

The sun cannot offer such guidance; its light is constant, unphased. The moon, however, carries both light and shadow, reflecting the sun’s illumination while revealing the passage of days. This relationship between light and darkness mirrors the balance of time itself, visible, measurable, and yet deeply mysterious.

What is especially beautiful about this system is its accessibility. The Islamic calendar was never simply confined to scholars or astronomers. Anyone, anywhere, could step outside, look up at the sky, and determine the beginning of the month. In that sense, the lunar calendar represents a democratisation of time, a sacred rhythm shared equally by all who observe the night sky.

When we look at ṣalāh itself, we find that the rhythm of our daily worship is bound to the cycle of the sun and its interaction with the earth. The very names of the prayers are, in fact, names of times — not merely labels for acts of devotion, but reflections of distinct moments within the day’s cosmic journey.

We know it is Dhuhr when the sun reaches its zenith — the point of stillness at the height of the day.

We know it is ‘Asr when shadows lengthen and become twice our height, signalling the day’s gradual retreat.

We know it is Maghrib when the sun dips below the horizon, giving way to dusk.

We know it is ‘Ishā’ when darkness settles fully and the light has faded from the sky.

Even Fajr, the dawn prayer, is not simply a time before sunrise but a moment of awakening, when the first light splits the horizon and creation stirs to life again.

In this way, prayer is more than a ritual act; it is a conversation with time itself, a sacred synchronisation between human life and the celestial order. Each ṣalāh anchors us within the natural cycles of the universe, reminding us that time, worship, and creation all move in divine harmony.

The cycles of prayer, the orbits of planets, the beating of the heart, the flow of blood, the rhythm of the tides, all are reflections of divine order. Even the Qur’anic vision of life itself is cyclical: “From Allah we came, and to Him we shall return.”

Rediscovering the Sacred Rhythm

We live in an age that prizes speed, efficiency, and data and yet we’ve lost touch with the natural and sacred rhythms that once guided human life. The mechanical clock, the sundial, the lunar month, all these remind us that time isn’t just to be measured, but felt.

Time is not a commodity to be spent; it is a trust (amanah) to be honoured. It is the most precious gift Allah has given us — once lost, never regained.

As a historian, I see time as both a record and a revelation. From Adam (alayhi salaam) to the present moment, and toward the Day of Judgment, time has always been part of our divine story as a journey through beginnings, endings, and eternal return.

Perhaps it’s time we slowed down and listened again to the ticking of the clock, the rhythm of our breath, the orbit of the moon and remembered that every moment is both fleeting and sacred.

“So blessed is He in whose hand is dominion, and He is over all things competent He who created death and life to test you as to which of you is best in deed.”

(Surah al-Mulk, 67:1–2)

Food not just for thought but for the yearning soul.

Thank you for this interesting article. While reading it, I was sure I would stumble upon a reference to Ahmed Haşim's masterful essay on Muslim experience of time, "Müslüman Saati". If you haven't read it before by any chance, you should do.